If Mark Zuckerberg could have imagined the worst possible outcome of his decision to insert himself into the 2020 election, it might have looked something like the

scene

that unfolded inside Mar-a-Lago on a steamy evening in early April.

There in a gilded ballroom-turned-theater, MAGA world icons including Kellyanne Conway, Corey Lewandowski, Hope Hicks and former president Donald Trump himself were gathered for the premiere of “Rigged: The Zuckerberg Funded Plot to Defeat Donald Trump.”

The 41-minute film, produced by Citizens United’s David Bossie, accuses Zuckerberg of buying the election for President Biden. Its smoking gun? The very public $419 million in grants Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan donated to local and state election officials in 2020 to help them prepare for the unprecedented challenge of pulling off an election in a pandemic. On the film’s poster, Zuckerberg is

pictured

smugly dropping a crisp Benjamin into a ballot box.

Suffice it to say, this was not exactly what Zuckerberg had in mind.

The Facebook founder had tried in vain to make his grand entrance into the election appear impartial. He didn’t plow tens of millions of dollars into a single candidate’s super PAC, like his buddy Dustin Moskovitz

did for Biden

. He didn’t spread his wealth between Senate campaigns, like his other buddy Peter Thiel

is doing right now

.

He did it the Zuckerberg way. The Facebook way. Instead of explicitly picking a party — God forbid he be the arbiter of anything — he threw open the vault to his vast fortune and said: Have at it, America. He

offered

grants to any election official who wanted one, so long as they spent it on what a lot of people would consider mundane essentials that make it easier and safer for everyone to vote: ballot sorters, drop boxes, poll workers and — because it was 2020 — hand sanitizer.

And when those election officials from red, blue and purple places, all starved for funding, applied for more money than the whopping $300 million he already offered, he kicked in another $119 million to satisfy the rest of the requests. Because the last thing he wanted was for anyone to claim they got stiffed and accuse him of bias. What a disaster

that

would be.

By almost

all accounts

, the funding from Chan and Zuckerberg was heaven-sent for the people — left, right and center — who actually had to carry out a historically high-turnout election in the midst of a pandemic when poll workers, many of them elderly, were risking their health by just showing up. And some of the equipment the money paid for should last cash-strapped local governments for years.

But a year and a half later, Zuckerberg now finds himself smack in the center of one of the 2020 election’s multitudinous conspiracies, this one with its own catchy name: Zuck Bucks.

The truth is, Zuckerberg’s attempt to appear neutral was a fool’s errand. Because at a time when Republicans are rapidly

restricting

access to the ballot box in states across the country, spending nearly half a billion dollars to do the exact opposite of that is tantamount to a partisan choice. Or, at least, it was bound to be viewed that way by

about half of the country

.

If anyone could have predicted that, it should have been Zuckerberg; the Zuck Bucks ordeal is in many ways the real world analog of the accusations of bias Meta has been facing for years. Much as Facebook’s efforts to combat hate speech have become synonymous in some circles with conservative censorship, expanding voter access has become equally synonymous with cheating. Both views lack substantive evidence to back them up, but that hasn’t much mattered. What’s true online is true in the real world: Turning the proverbial knob in any direction is only going to be viewed as neutral if you agree with the direction it’s turning.

As with seemingly everything Zuckerberg touches, the donations — and their ensuing backlash — have had disastrous unintended consequences, inspiring new restrictions on election funding in more than a dozen states, leading to death threats and harassment against the nonprofit leaders who distributed the money and contributing to the

resignations

of election officials who accepted it. The grants have been the subject of shambolic investigations and — as shown by what The Washington Post

described

as the “fraud fete” in honor of the “Rigged” premiere in April — have become a big part of the Big Lie.

Zuckerberg couldn’t have been naive to how his donation would be spun. But maybe he was willing to take his lumps. Or maybe he, like so many others, could never have imagined how bad things were actually about to get. Zuckerberg’s millions may have saved the 2020 election, but they’ve also become the beating heart of bad-faith efforts to undermine it — and future elections going forward.

‘How would you spend it?’

David Becker was on vacation with his family in the Outer Banks, in the socially distanced days of late August 2020, when Zuckerberg’s philanthropic organization, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, called him with a question that could have been plucked from a dream: “If you had a lot of money right now,” Becker remembers them saying, “how would you spend it?”

The election was two months away, and Becker, a former senior trial attorney for the voting section of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division and the current executive director of the nonprofit Center for Election Innovation & Research, had been talking to election officials about the severe funding gap they were experiencing. COVID-19 was writing and rewriting new rules for how Americans would cast their ballots in November and how those ballots would be counted.

Congress awarded

$400 million

through the Cares Act to help states navigate those changes, but it wasn’t enough. By the time he got the call in August, Becker said, “it was clear the government wasn't going to step in and perform or satisfy its responsibility.”

Becker told the person on the other end of the line that if he had money to spend, he’d offer it to election officials to help them educate voters on the onslaught of changes that were coming their way. “I had no idea of the scope of the funding,” Becker said. “I didn't know if they were talking about $100,000 or what.”

It was more like “or what.” A little over a week after Becker got the call, Zuckerberg and Chan awarded

$50 million

to Becker’s organization to distribute voter education grants to any state that wanted one.

The money ended up coming not from CZI, but directly from Chan and Zuckerberg’s personal funds, which they routed through the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. “Like most major philanthropies, we regularly consider a wide variety of grant-making opportunities for alignment with our organizational priorities,” CZI spokesperson Jenny Mack told Protocol. “In this case, Mark and Priscilla chose to make a personal donation to help ensure that Americans could vote during the height of the pandemic.”

Becker rushed to email every state election director in the country, encouraging them to apply. About two dozen took him up on it (though Louisiana eventually withdrew), collectively asking for even more money than the $50 million Becker had to offer. So he went back to the money well, asking Zuckerberg and Chan — or rather, their people — to kick in the

$19.5 million

difference so he wouldn’t have to turn anyone down. “I thought it was really important to use as little discretion as possible,” he said. “I’m very grateful that they agreed.”

All in, CEIR got nearly $70 million, the vast majority of which it passed on to 22

states

, plus Washington D.C. — from bright blue Massachusetts to bright red Missouri — in the full amount they had requested.

Tiana Epps-Johnson founded and is the executive director at the Center for Tech and Civic Life.

Photo: Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Tiana Epps-Johnson founded and is the executive director at the Center for Tech and Civic Life.

Photo: Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Meanwhile, about 1,000 miles away in Chicago, Tiana Epps-Johnson had been having similar conversations with the Zuckerberg-world. Her organization, the Center for Tech and Civic Life, did some work with Facebook during the 2016 election, helping the company with its

sample ballot generator

. One of Meta’s public policy managers, Maurice Turner, also sits on the group’s advisory committee.

Since 2016, CTCL had been focused on running cybersecurity training for election officials. That training had been licensed by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission under President Trump in 2020, and was offered to all election offices in the country.

But the COVID-19 crisis reoriented CTCL’s focus. Epps-Johnson had watched the Wisconsin state presidential primary, just one month into lockdowns. Nervous voters who had scarcely left their homes in weeks stood six feet apart in hours-long lines — and in some places, in a hail storm — waiting to cast ballots. Major cities had closed most of their polling places. Milwaukee, for example, usually

operates

more than 100 polling places; that primary day, the city was able to

open

just five. “We wanted to figure out how we could use any tool in our toolbox to support these folks,” Epps-Johnson said.

In July, two months before Chan and Zuckerberg announced their election grants, CTCL

awarded

$6.3 million in grants to the five biggest cities in Wisconsin to help them with early voting and voting by mail, PPE and poll-worker recruitment and training, among other things. From there, the organization spent the summer doling out additional grants to select jurisdictions in Pennsylvania and Michigan, as well as launching a

rural grant program

for areas CTCL said were “often overlooked in the national election landscape.”

But those early grants largely went unnoticed until September, when CTCL also got funding from Chan and Zuckerberg — a whopping $250 million worth. Suddenly, CTCL had the money to expand its earlier grant program to every jurisdiction in the country. “That moment is indescribable,” Epps-Johnson said.

According to Zuckerberg spokesperson Ben LaBolt, who is himself a longtime Democratic communications consultant, CTCL and CEIR got picked based on their prior track records of working with election offices. “The team conducted due diligence to see what nonpartisan organizations had helped fund election infrastructure in states and local election jurisdictions previously,” LaBolt said. “CTCL and CEIR were identified as organizations that had relevant experience.”

Unlike the CEIR money that went to states for voter education, CTCL’s portion of the money would be regranted to local jurisdictions to pay for things like poll-worker recruitment, ballot-processing equipment, drive-through voting, protective gear and more. The announcement

emphasized

, as if predicting the backlash to come, that the money would go to “urban and rural counties in every corner of America.”

Like Becker, Epps-Johnson also fielded more applications than she had the money to match, and she too was wary of turning anyone down. She went back to Zuckerberg and Chan for more, and got it. In all, CTCL used Zuckerberg and Chan’s money to award more than $330 million in grants to around 2,500 election departments in 47 states, including Washington D.C. More than half of those grants went not to big left-leaning cities, but to jurisdictions with 25,000 voters or less. Every district that asked for a grant got one. “Even our biggest dreams about what might be possible with this program, we were able to exceed,” Epps-Johnson said.

‘One enormous conspiracy theory’

But the sudden influx of cash from one of the world’s most divisive billionaires instantly thrust CTCL’s spending into the spotlight. Conservative critics conflated the early grant program that came out of CTCL’s budget with the Zuckerberg grants that came later, seizing on the idea that CTCL and Zuckerberg had conspired to give Democratic stronghold cities like Milwaukee and Philadelphia a head start before making additional funding available to everyone.

This detail is not only a big part of the plot of “Rigged,” but also central to an investigation in Wisconsin that has been seeking to “decertify” the election there. Michael Gableman, the special counsel leading that investigation, now refers to the first cities CTCL funded in Wisconsin as the “

Zuckerberg 5

."

“Why just pick the top five Democratic cities?” Gableman, who

received

a round of applause at the film’s premiere at Mar-a-Lago, asks in one scene in “Rigged.” “And then when they received criticism about that, then they sprinkled relatively minor amounts of money.”

In truth, Epps-Johnson said, before Zuckerberg and Chan made their donation, CTCL was in triage mode, spending its own modest operating budget on the places that were most likely to have a big problem on their hands come November. CTCL had been working with election offices in Michigan and Pennsylvania even before COVID-19, as both states had expanded access to voting by mail well before the pandemic began. Once COVID-19 hit, Epps-Johnson said, CTCL focused its attention and its grants on the counties in those states that were both struggling to contain the virus and bound to see the biggest influx of mail-in ballots. “In nearly every place, that leads you to population centers,” Epps-Johnson said.

The early grants weren’t the only reason CTCL had a target on its back, though. While the organization is nonpartisan, with both Democrats and Republicans sitting on its board, it’d be hard to claim the same about Epps-Johnson, a former Obama fellow, who, along with her co-founders, had worked at the progressive New Organizing Institute before launching CTCL. When former President Obama gave

his April speech

about disinformation, it was Epps-Johnson who introduced him and welcomed him to the stage with a hug.

Becker, too, had at least some progressive bona fides. While he’d spent nearly a decade at nonpartisan Pew Charitable Trusts, where he oversaw election initiatives, he’d also done a brief stint as a

senior staff attorney

at People for the American Way, a progressive advocacy group that now describes itself as being “founded to fight right-wing extremism.”

If Chan and Zuckerberg erred at all in their efforts to appear impartial, it was in selecting organizations to accept the money whose founders’ resumes could easily double as Steve Bannon’s dartboard. Republicans argue that was a feature of Zuckerberg’s plan, not a bug.

An avalanche of lawsuits soon followed. In Louisiana, Attorney General Jeff Landry barred election officials from accepting the money they’d been granted and sued CTCL,

alleging

it had engaged in an illegal “financial contribution scheme.” In nine other states, The Amistad Project, which would go on to join the Trump campaign in challenging the election results, also

backed

lawsuits to block the grants from going through. “It was really clear there were legal challenges that were misinformation campaigns that were designed to undermine voter confidence,” Epps-Johnson said.

Zuckerberg himself made a rare statement about the suits in October 2020. “Since our initial donation, there have been multiple lawsuits filed in an attempt to block these funds from being used, based on claims that the organizations receiving donations have a partisan agenda,” he

wrote

in a Facebook post. “That's false.”

One by one, the suits were dismissed. In one Colorado case, a district judge even imposed sanctions on the attorneys who filed the suit,

calling

their complaint “one enormous conspiracy theory.” Only the Louisiana case still stands, after the dismissal was

reversed

on appeal in April 2022.

But the grant program’s court victories hardly stopped the Zuck Bucks theory from metastasizing and transforming from a nuisance into something a lot more menacing. CTCL was bombarded with death threats, forcing the company to spend $180,000 on security in the last months of 2020 alone.

Becker of CEIR got a few threats, too, but whatever he dealt with, Becker said, “it’s nothing compared to what local election officials in cities and counties are experiencing.”

‘The consequences of telling the truth’

On a Thursday afternoon last year, Al Schmidt walked into a farmer’s market in a northwest corner of Philadelphia for what had to be his umpteenth interview, wearing a mask that read “VOTE” in big block letters. It was December of an off-cycle year, but such is Schmidt’s commitment to the role he now fills as defender of the franchise.

The former Philadelphia City Commissioner was among the election officials in the belly of the Pennsylvania Convention Center in November 2020, working around the clock and not returning home for days as ballots were counted and protests raged out front. At the time, and still to this day, Schmidt, who’s been a registered Republican since the ‘90s, has delivered the same message: that the 2020 election was legitimate, but that the future of elections is in jeopardy.

For that, Schmidt was called a

RINO

by Trump on Twitter. And for that, Schmidt and his family have faced merciless harassment and targeted threats, which temporarily forced his wife and two kids to move in with family while Schmidt had a security system installed in their home. For months after the election, police escorts followed the family from the grocery store to the sledding hill. “The consequences of telling the truth aren’t easy,” Schmidt said. “That doesn't mean you shouldn't tell the truth.”

Schmidt is one of the

many election officials across the country

who have resigned from their positions since 2020. It was a transition he’d planned well before the 2020 election, but he said, “2020 certainly confirms in my mind that it's the right decision for my family.”

Philadelphia received a little over $10 million from CTCL, the most of any county in the hard-fought state of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia is by far Pennsylvania’s biggest county, so it stands to reason it would also get the biggest check. But the grant program’s conservative

critics

, including some Pennsylvania

lawmakers

, argue it’s not just that Philadelphia and other counties Biden won in Pennsylvania got more money in total. It’s also that they got more money per voter.

“Counties won by Biden in 2020 received an average of $4.99 Zuckerbucks per registered voter, compared to just $1.12 for counties won by Trump,” reads one

analysis

on Pennsylvania by the

right-leaning think tank

Foundation for Government Accountability. Other reports have looked at CTCL’s spending in

Texas

,

Florida

and

Georgia

and reached similar conclusions

These reports have their own partisan roots. The Pennsylvania analysis was authored by a former Department of Labor official under Trump. Another

report

on Zuckerberg’s spending in Texas comes from an organization whose board includes, among other prominent Trump supporters, John Eastman, the Jan. 6 leader who

pushed

Mike Pence to reject the election results. Still

more

articles

arguing Zuckerberg bought the election for Biden have been published by a new think tank called The Caesar Rodney Institute for American Election Research, whose primary

purpose

appears to be exposing the bias behind the CTCL grants. “Even if it wasn't partisan in its intent, and I would argue that it almost certainly was, it was certainly partisan in its effect,” said William Doyle, a former University of Dallas economics professor, who co-founded Caesar Rodney with an anonymous partner he described as his “shadow conspirator.”

Whatever the political motivations of their authors, anyone can see that the spending numbers do look lopsided. “Rigged” makes this the centerpiece of its argument. But what these analyses miss, Schmidt argues, is what’s behind those numbers. In elections, scale doesn’t necessarily drive down costs. “In a smaller county, if they have a [turnout] increase, they might be able to hire, you know, five more people to sort ballots by hand,” Schmidt said. But in a city like Philadelphia, that received 375,000 mail-in ballots in 2020, you need machines. And machines cost money — sometimes, a lot of it.

About half of the CTCL grant went toward equipment costs in Philadelphia, including the purchase of two ballot sorters that reportedly

cost more than $500,000 each

. It’s a similar story in states across the country that have been the subject of conservative scrutiny. “It’s no doubt that cities are going to be a little more expensive than rural areas in terms of their needs,” said Nate Persily, a professor at Stanford Law School and co-founder of the Healthy Elections Project. It also just so happens that cities across America tend to vote for Democrats.

In Philadelphia at least, the Zuckerberg money was essential, Schmidt said. He’d seen during the primaries how the slower-than-usual process of counting ballots was creating opportunities to exploit uncertainty among voters. “All that equipment allowed us to really speed up the whole process,” Schmidt said. That includes the process of comparing mailed ballots and in-person poll books to ensure people weren’t voting twice. And that equipment will continue to benefit Philadelphians, he said, “as long as that equipment keeps working.”

Al Schmidt, a former Philadelphia City Commissioner, is one of the many election officials across the country who have resigned from their positions since 2020.

Photo: Lynsey Addario/Getty Images

Al Schmidt, a former Philadelphia City Commissioner, is one of the many election officials across the country who have resigned from their positions since 2020.

Photo: Lynsey Addario/Getty Images

Of course, none of that stopped people — including one very powerful person — from exploiting the uncertainty of it all anyway. “Very few of us who work in this space were prepared for the degree to which the losing candidate would continue to lie to their supporters and, in so doing, continue to weaken American democracy, just to keep the anger going and the donations coming,” said Becker, who is now running a pro bono legal defense

network

to help election officials fend off frivolous prosecution and harassment.

What bothers Schmidt most about the backlash to the grants is the notion that Zuckerberg alone created an imbalance or a distortion of the electoral system. He calls that line of argument “deceitful” because, in a country where elections are run and financed at the local level, there’s never been balance to begin with. “If Philadelphia wanted to spend $100 million on elections, it could,” Schmidt said. “There is no equality from county to county.”

It’s why studies show that

districts

with more minority voters often have fewer voting machines, leading to longer lines. Those studies have hardly animated conservatives the way the Zuck Bucks studies have. There are obvious partisan reasons for that. Underfunding elections in minority districts tends to hurt Democratic turnout. Funding elections in those districts, as Zuckerberg did, well, doesn’t.

But there’s another reason why the Zuck Bucks debacle is different. While the chronic starvation of election officials is a perpetual problem with plenty of blame to go around, this unprecedented

funding

of an election can be traced back to a single perfect villain: the Big Tech billionaire who conservatives believe has had it out for them all along.

‘Government should have provided these funds’

Anyone investing in voting access is bound to face opposition from the right. But the other big reason why Zuckerberg’s attempt to appear neutral was doomed from the start is because Zuckerberg is not seen by either party as anything close to a neutral figure. He’s somehow both the guy who got Trump elected and placated his administration

and

the guy who censored and conspired to defeat him. Nothing Zuckerberg does gets to be impartial. The $419 million he spent in 2020 ensures it never will be again.

Try though he did to ingratiate himself with the right throughout the Trump years, Republicans already decided long before he spent a penny that his all-powerful company had rigged the election against them. Or, at least, they decided it was in their interest to say so in order to raise money off the message and spook Facebook out of stifling the speech of the party’s most extreme factions — and its leader.

Then, of course, there’s the fact that Zuckerberg’s personal politics, if not his professional politics,

have

tended to lean left. He’s spent millions on causes like

immigration reform

and

criminal justice reform

. His spokesperson recently came off of Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation team, and the person leading CZI’s policy operation, David Plouffe, was President Obama’s campaign manager. (CZI said Plouffe wasn’t involved with the grant program).

That Zuckerberg was the boogeyman coughing up half a billion dollars to expand voting access almost made it too easy for the right to argue those kinds of donations should be forbidden altogether. Note the

absence of outrage

over the millions of dollars Arnold Schwarzenegger also spent in 2020, on a similar grant program that was, in fact, far more selective than Zuckerberg’s.

Zuckerberg’s election donation sparked a conservative scramble not just to prevent his money from being spent in 2020, but also to prevent anyone from personally spending money on any election ever again.

Since 2020, some 14 states have

passed laws

forbidding private funding of elections. Similar bills have passed the legislature in another five states, including Pennsylvania, but have been blocked by Democratic governors. The conservative group Heritage Action for America has

backed

these bills with a $10 million investment spread across eight states. ”There is nothing more important than ensuring every American is confident their vote counts — and we will do whatever it takes to get there,” Jessica Anderson, executive director of Heritage Action, said when the investment was announced.

The Zuck Bucks theory was key to getting these laws passed. First you plant the seed of distrust, then you promise to nip what you planted in the bud.

The irony of that is that Becker, Epps-Johnson, Schmidt and even Zuckerberg himself all tend to agree that individual donors shouldn’t be the ones funding elections. After all, Zuckerberg may have been assiduously nonpartisan in his giving last time around, but he didn’t have to be. There was nothing stopping him from publicly picking favorites if he’d wanted to. And most everyone agrees that’s hardly a way to ensure trust or equity in the system. Zuckerberg even said as much in his October 2020 Facebook post about the grants. “[G]overnment should have provided these funds, not private citizens,” he wrote at the time, not missing the chance, for once, to rap Congress on the knuckles for not doing

its

job.

Center for Election Innovation & Research executive director and founder David Becker had spoken to election officials about the severe funding gap they were experiencing.

Photo: Joshua Roberts-Pool/Getty Images

Center for Election Innovation & Research executive director and founder David Becker had spoken to election officials about the severe funding gap they were experiencing.

Photo: Joshua Roberts-Pool/Getty Images

The problem is, the government didn’t provide those funds. With the midterm primaries now underway and the pandemic ongoing, it still hasn’t. That leaves some states now underfunded and unable to raise funding from anywhere else.

“What we're seeing is no ability for philanthropy to step in in the ways that they would if there was a struggling library or a school,” Epps-Johnson said of the laws being passed across the country, “and also no additional public funding at a time when we have election officials using technology that they purchased before the iPhone was invented.”

“We can’t both defund them and restrict their ability to get other funds,” Persily of Stanford said.

In his most recent budget, President Biden called for what would be a historic

$10 billion investment

in election infrastructure over the next 10 years. CTCL has been pushing for double that investment over the same period of time. But so far, Congress has shown little indication it’s going to act.

That’s one reason why Epps-Johnson’s new focus has been on helping election officials help each other through a group called the U.S. Alliance for Election Excellence. It will invite election officials from every district in the country to come together and swap expertise, and is

backed by

$80 million, some of which will go to election administration grants in states where that kind of thing is still possible.

But this time, the money’s not coming from Zuckerberg.

The man who spent years atoning for his company’s failure to secure the 2016 election — then rushed to the rescue of the 2020 election — appears to be taking a step back from politics. Or at least, he’s trying to. He made that much clear when he promoted Nick Clegg to president of Global Affairs at Meta earlier this year, freeing Zuckerberg up to post even more

legless videos

of himself inside the metaverse he’s desperately trying to build. Since then, Zuckerberg has been more quiet than usual about the political events of the day, even letting Clegg take the lead after Meta was banned throughout Russia.

So despite the breathless headlines, it wasn’t any big surprise when LaBolt

said

last month that Zuckerberg wouldn’t be making any new grants this year. Citizens United’s Bossie, for one,

celebrated

the news as a “major victory.” In truth, LaBolt said, the grants were always meant to be a one-time deal.

But Zuckerberg can’t just walk away from this ordeal so easily. Like Cambridge Analytica and the Russian troll scandal before it, Zuck Bucks seems likely to hover over Zuckerberg, and Meta, for years, regardless of whether he makes any more donations. Whatever moves Meta makes in the midterms and beyond — including deciding whether to reinstate Trump’s account — this supposed scandal will be just another data point used to pressure Meta to bend to one party’s will.

A year and a half since polls closed in November 2020, Zuck Bucks remains one of the 2020 election’s most enduring conspiracy theories. It’s grown beyond what Trump and his acolytes say happened in 2020, and has now formed the basis of predictions about what will happen this year and two years from now. “They're gonna try and do it again and ‘22 and ‘24,” Trump says in “Rigged.”

Of course, what no one mentions in that film is that preventing private donors from funding ballot sorters and drop boxes won’t free U.S. elections from the unchecked influence of tech billionaires. If anyone understands that, it’s the folks at Citizens United who won the Supreme Court case to make it so. The midterm elections and the presidential race in 2024 will still be awash in tech money, and some of the very

people

who were in that screening room at Mar-a-Lago are already happily accepting it.

It’s just that, instead of paying for poll workers, tech money will cover the cost of attack ads and “

strategic litigation

” funds to take out members of the media. The money won’t be announced in press releases or disclosed in public reporting, and it won’t be offered up to everyone, regardless of party. It’ll flow into partisan dark-money groups that don’t disclose their donors and that work hard to hide their footprints. It’ll still be there. It’ll just be harder to find. Who knows? It may even wind up financing a film some day that tries to convince the world the election was rigged. And it may even work.

Tiana Epps-Johnson founded and is the executive director at the Center for Tech and Civic Life.

Photo: Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Tiana Epps-Johnson founded and is the executive director at the Center for Tech and Civic Life.

Photo: Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Al Schmidt, a former Philadelphia City Commissioner, is one of the many election officials across the country who have resigned from their positions since 2020.

Photo: Lynsey Addario/Getty Images

Al Schmidt, a former Philadelphia City Commissioner, is one of the many election officials across the country who have resigned from their positions since 2020.

Photo: Lynsey Addario/Getty Images

Center for Election Innovation & Research executive director and founder David Becker had spoken to election officials about the severe funding gap they were experiencing.

Photo: Joshua Roberts-Pool/Getty Images

Center for Election Innovation & Research executive director and founder David Becker had spoken to election officials about the severe funding gap they were experiencing.

Photo: Joshua Roberts-Pool/Getty Images

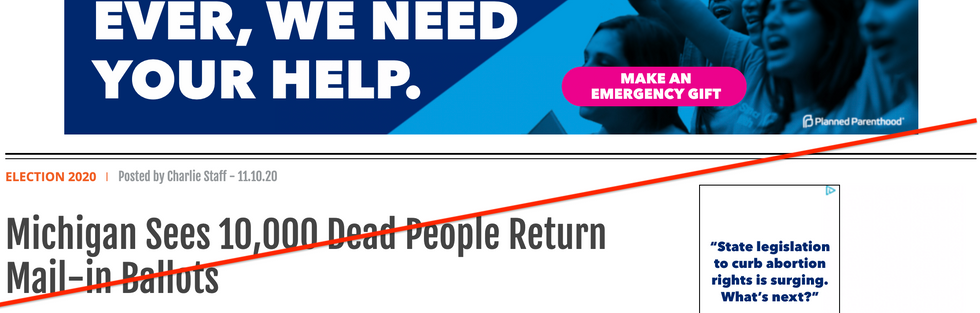

A Planned Parenthood fundraising ad appears on a story containing election misinformation at the top of Charlie Kirk's website.

Screenshot: Protocol

A Planned Parenthood fundraising ad appears on a story containing election misinformation at the top of Charlie Kirk's website.

Screenshot: Protocol

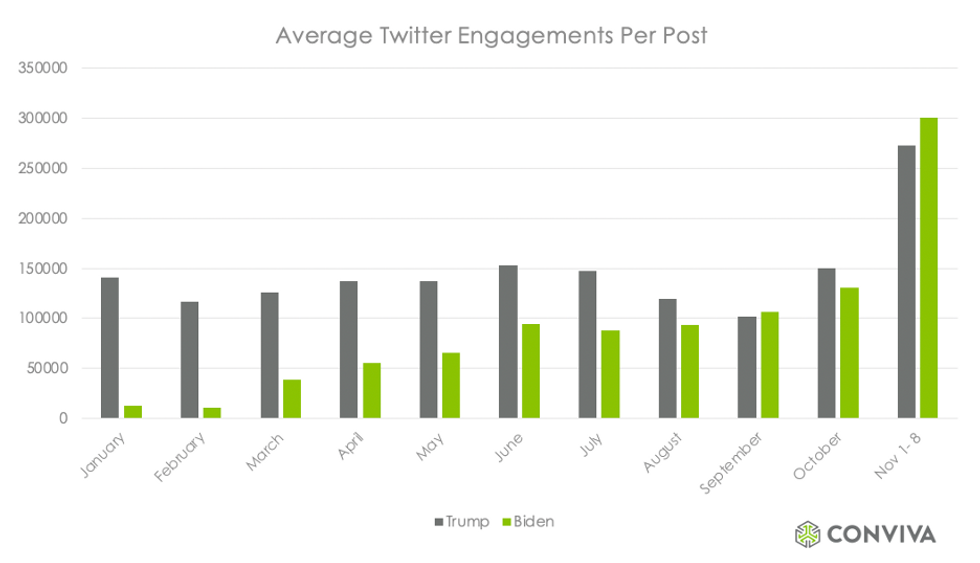

Image: Conviva

Image: Conviva

Image: Conviva

Image: Conviva

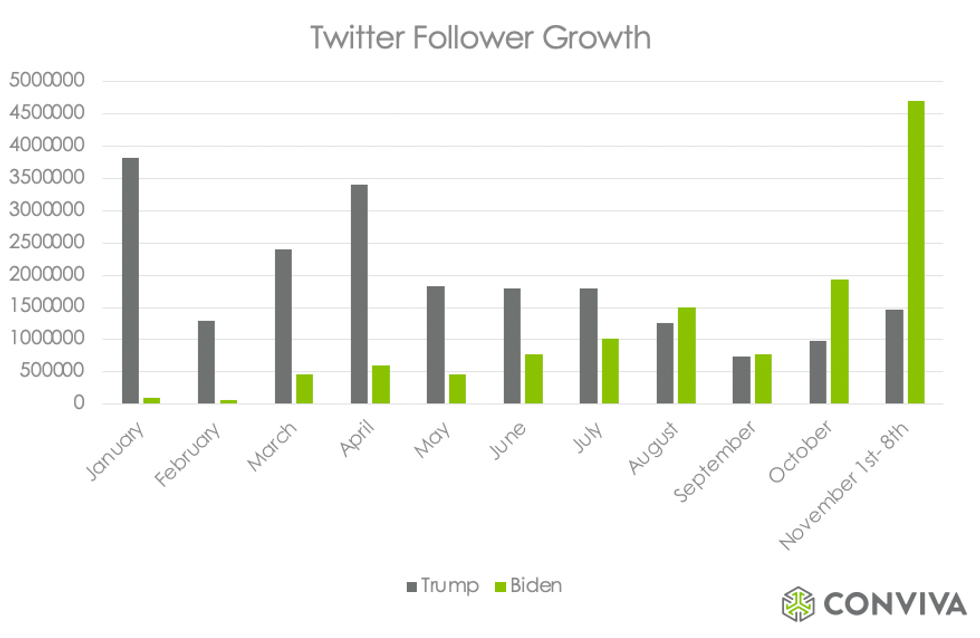

Image: Conviva

Image: Conviva