Peter Idah had met Kelsey Hightower before. But this time, he brought his son.

It was March 2016, and the Kubernetes jamboree, KubeCon, was coming to Idah's hometown of London for the first time. Hightower, the de facto spokesperson for Kubernetes just as it was emerging as a force in enterprise tech, was speaking at the event.

Idah had watched many of Hightower's talks and demonstrations on YouTube, as a veteran engineer trying to learn new skills like Puppet and Kubernetes. Now, he wanted his son Jovanni to meet Hightower, to see that Black people like themselves could be leaders in a field that has become the driving force behind the modern economy.

"What I told him was, the first time I saw his video, it struck a chord in me that just touched me in a way I didn't expect," Idah told Protocol. "What was really surprising to me was that I never knew I needed that. Because I was confident; I didn't know I needed to see somebody who looked like me [leading those discussions]."

Now, Hightower, principal engineer for Google Cloud, is one of the most prominent and respected faces in cloud computing and open-source software. He has been one of the most popular speakers at enterprise tech events for several years, marrying formidable self-taught technical chops to a storyteller's voice.

He also stands out as one of the few Black men in enterprise infrastructure tech, a group whose members feel is an even whiter domain within the notoriously homogenous tech industry. For reasons that should be clear, his path to a prominent role in this field has been that much harder.

There's no way a Black guy got there by accident.

"He didn't get there by accident. There's no way a Black guy got there by accident," said Bryan Liles, a principal engineer at VMware and a friend of Hightower's who has also dealt with issues of racism as a Black engineer in the tech industry. "We didn't grow up near Stanford," he added, underscoring the role that the exclusive Silicon Valley university played in launching Google and many a tech career.

Hightower, 39, was fairly well-known in and around the Docker and Kubernetes open-source communities as those technologies emerged around the middle of the last decade, but really caught people's attention with a talk at a tech conference in May 2017 , in which he broke from the usual pattern of highly technical how-to presentations to tell his life story.

His brief encounter a year earlier with Idah, who now works for rising enterprise star HashiCorp, had left quite an impression.

"He's watching YouTube trying to figure out all this new stuff," Hightower recalled. "And here's this guy that looks exactly like him. And I know what I'm talking about, and other people say he knows what he's talking about. And he told his son that he wanted just to show him that not only are we allowed to attend the event, we can lead them."

'You have something that I don't'

Kelsey Hightower has always been a leader.

He spent his early childhood in Long Beach, but his mother decided to move back to family and friends in their hometown of Atlanta following a divorce, right as Hightower was entering high school. Sports had been his obsession up until that point, but he decided he should probably get a job to help out around the house and pay for his own clothes.

He began working at McDonald's, earning $4.15 an hour working nearly 40 hours a week, mostly on the weekends. He was quickly promoted to shift manager at the age of 16, where he had the authority to tell other workers when they could clock out on slow nights, and walked the two miles from his house to the restaurant before every shift.

"They had that place working like clockwork," recalled Ronnie Jordan, a childhood friend. "He figured out how to do stuff way more efficient early."

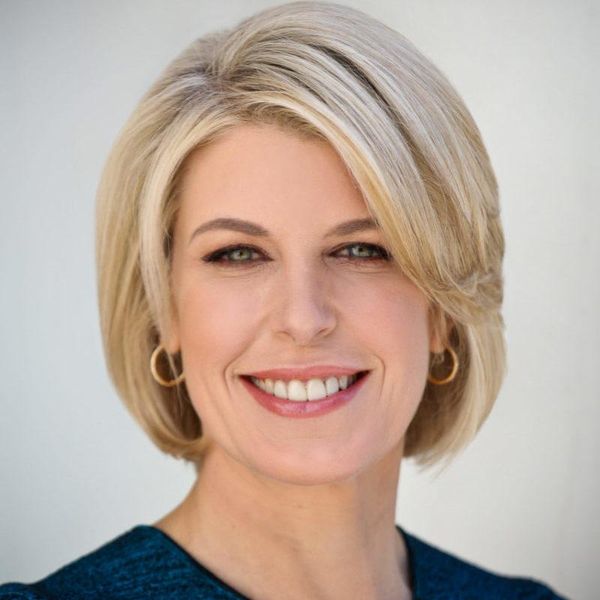

Kelsey and Klarissa Hightower attend Homecoming their senior year in high school. They would marry in 2006.

Photo: Kelsey Hightower

Kelsey and Klarissa Hightower attend Homecoming their senior year in high school. They would marry in 2006.

Photo: Kelsey Hightower

Hightower was also an excellent student. After a brief stint at Clayton State University, where he said the technology classes were more or less glorified Microsoft Word tutorials, he realized he needed a bigger challenge. He enrolled in certification classes sponsored by CompTIA to get his A+ certification, which led to a job as a DSL installation technician for Bell South at the age of 19.

"In my 12th-grade year I said, you know what, maybe this technology thing is a thing, right? You're looking at the stories of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, they didn't go to college. You know, the richest man in the world didn't go to college," Hightower said.

It was while working for Bell South in the early 2000s that Hightower had an experience that would shape the rest of his life, a story he told in that pivotal 2017 talk.

He was dispatched to a nice neighborhood in Atlanta for a standard DSL installation. When he entered the home, he realized the customer was someone prominent; he was an architect and city planner, with pictures of himself and several U.S. presidents lining the walls of the office where Hightower was installing the internet connection.

The customer shocked Hightower by declaring right away that a Black person had never stepped foot inside his house. "But you're the only person that can give me this technology right now," he remembered the man saying, "so I'm going to put all that aside, because you have something that I don't."

"And at that point, it kind of clicked for me: This particular skill set was my Superman suit," Hightower said. "When I'm wearing the collared shirt with the tool bag, people will respect me for my talents and look past the other stuff. I kind of knew at that point that technology was this super empowering, leveling-the-playing-field skill that I could do."

A startup and a standup

After working as an independent contractor for Bell South for a few years in the early 2000s, Hightower realized that he was pretty good at this job. Customers began asking him for assistance that went beyond the scope of the usual technician's role, like setting up a network for a small business.

And at a certain point it dawned on him that he could probably make more money working for himself. In his early 20s, he started a solo practice as an IT consultant, eventually hiring others to work for him and opening up a store in Jonesboro, Georgia.

Indeed, if there's a word to characterize this stage of Hightower's career, it's "hustle." After running his own business for a few years, he actually briefly took a low-level tech job at Google and later the Georgia-based financial software company Total Systems (now named TSYS and owned by Global Payments).

And alongside those roles, for several years he also dabbled with a gig that taught him a lot about being onstage, dealing with pressure and the importance of getting paid.

Kelsey Hightower managed a comedy act.

Hightower co-chaired four of the first KubeCon events, which grew from a couple hundred engineers in 2015 to over 12,000 at KubeCon 2019.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

Hightower co-chaired four of the first KubeCon events, which grew from a couple hundred engineers in 2015 to over 12,000 at KubeCon 2019.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

Ronnie Jordan was getting some attention in the local Atlanta open-mic comedy scene when he and Hightower realized he might actually have a future making people laugh. The two began to work closely together on an act, and Hightower — the only person Jordan knew with a reliable car — started driving him around to different gigs around town.

When Hightower realized that not only could Jordan slay the crowds at the Uptown Comedy Corner — arguably one of the most influential Black comedy clubs in the South at that time — but that he could also make people howl with laughter at Jillian's, the suburban Dave-and-Buster's-like attraction favored by white people, he knew Jordan had potential.

He set up a studio where Jordan could practice his act. He filmed that act and posted it on the web, at a time when very few people understood the potential the web would have to launch entertainment careers. And he encouraged Jordan to try out for an "American Idol"-style comedy show produced by the team behind the "Kings of Comedy" series in 2004.

Jordan wound up making the finals and performing before 35,000 people at New York's Madison Square Garden. He won among strong competition and got $35,000 — minus Hightower's management fee, of course.

As a result of his performance, Jordan received offers from other acts to open at shows across the country, but he still only knew one guy with a reliable car. Hightower and Jordan drove across the country from gig to gig in a Chevy Suburban, and even during those long trips, Hightower found time to learn more about his budding career in computer science.

"He was always stopping at a Barnes and Noble" to pick up some new certification book for a nascent technology, said Jordan, who continues to practice comedy during a pandemic that has curtailed opportunities for performers of all kinds. "He would read a whole book in one night."

But Hightower learned more than tech during that experience.

"In the entertainment business, you get paid based on perception," he said. "And I think that's what I learned; it's not about the job, it's about what I bring to the job."

Searching for 'Geordi La Forge'

Meanwhile, Hightower was starting to get noticed in the Atlanta open-source community thanks to a series of talks at Python meetups when he caught the attention of James Turnbull, an engineering manager for infrastructure management pioneer Puppet Labs.

Turnbull was struck by the way Hightower and his colleagues at Total Systems were using Puppet, Python and some good old-fashioned hacking to transform how Total Systems deployed software changes to its servers.

"This was real shadow IT," said Elson Rodriguez, a colleague of Hightower's at Total Systems and longtime friend. The financial services company still relied on mainframes and required employees to work overnight to deploy changes manually out of a Word document, which didn't sit right with Hightower and Rodriguez. So they worked together after hours to automate the deployment of those changes, and, despite internal obstacles and Rodriguez's (by his own admission, at the time) overly headstrong attitude, eventually saved the company countless hours each time new software rolled out.

"His optimism is just crazy," Rodriguez said. "He's lucky, because some people are optimistic and don't have the energy to see it through and process those lessons. He talks some crazy stuff, and tries some crazy stuff, and doesn't get too upset when it doesn't work out, he just draws a lesson from it and moves on."

Hightower was invited out to Puppet's headquarters in Portland, Oregon, to give a talk during the company's annual developer event in front of the whole company, including founder and CEO Luke Kanies. Puppet wound up offering Hightower, at the time a systems administrator, a job as a customer-facing software engineer.

"My guess is we can't name anybody else we hired in that same position," Kanies told Protocol. "He was great with people, but he was so much greater at talking about things," or explaining how customers could use Puppet's technology to solve their problems, he said.

Hightower collaborated on a popular book with Joe Beda and Brendan Burns, two of the original creators of Kubernetes.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

Hightower collaborated on a popular book with Joe Beda and Brendan Burns, two of the original creators of Kubernetes.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

After a few months of working remotely from Atlanta in 2013, Hightower made the cross-country move to Portland, a place about as geographically, culturally and racially removed from Atlanta as you can get in the U.S. It was early in his Portland days when Hightower got a reminder of what it was like to be the only Black man in a very white tech company.

At the time Puppet decided to build a digital hub called The Forge, where employees, customers and open-source contributors could share packages of Puppet code. As part of his transition from system administrator to software developer, Hightower wound up as the leader of the team responsible for this effort.

Individual teams at Puppet would give themselves funny or clever names; the team working on migrating Puppet to Windows was called "For the Win," as an example. One senior Puppet executive suggested that the team Hightower led should be named "Geordi La Forge."

He talks some crazy stuff, and tries some crazy stuff, and doesn't get too upset when it doesn't work out.

If you're unfamiliar with that name, as Hightower was at the time, know that Geordi La Forge was the only Black member of the crew of the Enterprise in "Star Trek: The Next Generation," a late 1980s television series that was incredibly popular with white Generation X tech workers.

"I actually go to my desktop, and I start searching for his name and it's, like, wait a minute! This is the only Black engineer on 'Star Trek'! Like, how did y'all pick that name for my team?" Hightower remembered, laughing as he did. At the time he took it in stride, even changing his Twitter profile picture to a picture of the character to tweak his new colleagues, making them initially nervous that they had offended him.

Both Hightower and Kanies recalled the story with humor, and it doesn't appear that there was any ill will on the part of the executive who suggested the name. But the term "microagression" was not as widely understood eight or so years ago, Kanies allowed.

"If you'd gone back to me at that time, I'd say I was much less aware of the struggles in general," Kanies said.

Rise of the container

Hightower is grateful for his time at Puppet, which introduced him to a much wider tech audience, got him involved more closely with the open-source community, and started him down the path toward becoming one of the more sought-after speakers on the cloud circuit.

But around 2014, he realized that Puppet's main business at the time — selling configuration management software to companies running their own data centers — was about to be transformed by two breakthroughs in infrastructure technology: the Go programming language and Docker containers.

Back at Google, the company had been refining Go as a modern update to the concepts behind C++, one of the most widely used infrastructure languages at that time. Like Rust , another programming language developed around this time, Go simplified some tasks and made it harder for programmers to make memory-handling mistakes that cause security holes.

Containers have been part of Unix and Linux for a long time, allowing developers to turn applications into portable packages for faster, easier deployment across different types of servers, both in-house and on the cloud. However, in 2013, Docker introduced a user-friendly way to take advantage of container technology, and demand exploded: Docker containers became one of the fastest-adopted new enterprise technologies in memory, and, while the company has struggled , the technology underpins the modern "cloud native" movement.

Hightower was fascinated by the concept from the moment he heard about it. "What if we changed the abstractions to be less about Linux and various programming languages to this thing called containers? That really piqued my interest," Hightower said. "I knew that I wanted to head in that particular direction."

Hightower speaks at KubeCon 2017 in Austin, Texas.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

Hightower speaks at KubeCon 2017 in Austin, Texas.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

After a brief stint at a Portland startup called Monsoon Commerce where he wrote his first open-source project, a configuration management tool called

Confd

, he joined another startup called CoreOS in early 2014. CoreOS developed a rival container format to Docker's and wound up becoming a key contributor to Kubernetes, the open-source container-management project born out of Google that would change Hightower's life.

"I wasn't a founder of CoreOS, but I played a role that became very instrumental to the company's success," Hightower said. "I think that kind of cemented me as an individual, my ability to make change no matter the environment."

Hightower stayed at CoreOS for a little over two years (the company was later acquired in 2018 by Red Hat just before IBM's acquisition of Red Hat), learning what it took to run an enterprise technology business.

During that time, Hightower embraced Kubernetes, traveling the world speaking at developer conferences large and small evangelizing this project. Outside of co-founders Joe Beda, Brendan Burns and Craig McLuckie , he quickly became one of the most recognizable faces of the project, which was quickly gaining converts as the best way to manage large clusters of containers at scale.

Hightower wound up collaborating with Beda and Burns on a book called " Kubernetes Up and Running, " which was published in 2017 and introduced him to a wider technical audience, setting the stage for Kubernetes to become one of the most influential open-source projects of the container era and a key building block for modern tech infrastructure.

"The whole Kubernetes and cloud-native journey has been full of an amazing amount of drama, it's tested all of us," said Beda, now a principal engineer at VMware who happened to be standing next to Hightower in London when he encountered Idah. "And through all of this, I've been incredibly impressed with Kelsey rising above it and really consistently being a stand-up person."

Taking a human touch to Google

At first Hightower wasn't entirely sure about joining Google, despite entreaties from some prominent members of the Kubernetes community. The project originated at Google, but it grew quickly as part of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, created in August 2015 by Google and other partners as a subset of the Linux Foundation .

In 2015, he was in talks with members of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California involving a possible role there, and he hesitated about joining Google because of "the fear of being put in a box. I had never met any company that could afford to let someone be who they were outside of a HR, well-defined job definition," he said.

Hightower actually rejected Google three times, but as he would come to learn, Google, of course, can afford lots of things.

"Google just had such a competitive story, long term," he said. "I talked to the NASA team, and they said, 'Look, Kelsey, it's going to take us 10 years to get to Mars, probably longer. Go to Google. If it doesn't work, we'll be happy to have you here at NASA.'"

Hightower officially joined Google in November 2015, and five years later, it's working out pretty well for both parties.

The company, which built some of the most impressive distributing computing architecture in the world during its rise to prominence, has struggled to empathize with the average cloud buyer , who doesn't need to do things Google's way. Along with serious technical skills, Hightower brought a more human touch to the developer relations role that all cloud vendors employ in an effort to get rank-and-file engineers excited about their services. Now, he spends most of his time talking to customers, figuring out what they really need from their cloud provider, and bringing those insights back to the product development team to improve Google's services.

Hightower is "leading by influence, and that is a difficult skill to develop," says one of his colleagues.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

Hightower is "leading by influence, and that is a difficult skill to develop," says one of his colleagues.

Photo: CNCF at KubeCon

Eric Brewer, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley and vice president of infrastructure at Google, says that Hightower's approach is "super authentic," which surely helps. "One thing Kelsey and I share is that we are not leading by authority," Brewer added. "I have no direct reports, he has no direct reports; we are leading by influence, and that is a difficult skill to develop."

That's especially difficult inside a company like Google, which has world-class talent working on some of the industry's most difficult problems.

"In college football, you've got the Heisman winners, but when you go to the NFL, you're a rookie all over again. When you go to Google, just the sheer amount of experience they have with large problems, you have to work hard to be creative," Hightower said.

Hightower has also played a prominent role in the rise of the CNCF. He co-founded the KubeCon conference in 2015 before the CNCF took over the event the following year, and he co-chaired four of the first events, starting with a gathering of just a few hundred infrastructure geeks and growing into a massive event in San Diego last November that attracted 12,000 people.

Those early KubeCons "very much set the tone for the community," said Liz Rice, vice president of open-source engineering at Aqua Security and co-chair of several KubeCon events in 2018, including the European event in Copenhagen she co-chaired with Hightower. "I can't really think of a better person to introduce me to what that role was all about."

You need a little bit of everyone

Today, Hightower is something of a legend inside the world of cloud tech, one of the most sought-after speakers and recognizable faces in the industry. But that wasn't always the case.

There was the conference held by a company where he'd been asked to deliver a keynote speech, and employees of that company kept asking him where to find the green room and where the drinks were being served. There was another conference where Hightower was scheduled to moderate a panel, and a Fortune 500 executive who was also going to be on the panel didn't recognize Hightower. He asked him for directions to the event, making for a very awkward moment when they met again backstage.

"After the second time, I kind of realized, without the name, without the name recognition, the stereotype is still with you. That's how people see me," Hightower said.

The tech industry has belatedly tried to fix its diversity problems , but its meager efforts are starting to get pushback both internally and at the highest levels of government.

Hightower currently sits on an internal council at Google focused on inclusion and retention, which has been a problem for the company over the last few years. He was initially reluctant to participate in those types of efforts, given the massive challenges presented by hundreds of years of structural racism and the physical and emotional labor that tends to get dumped on BIPOC employees at tech companies.

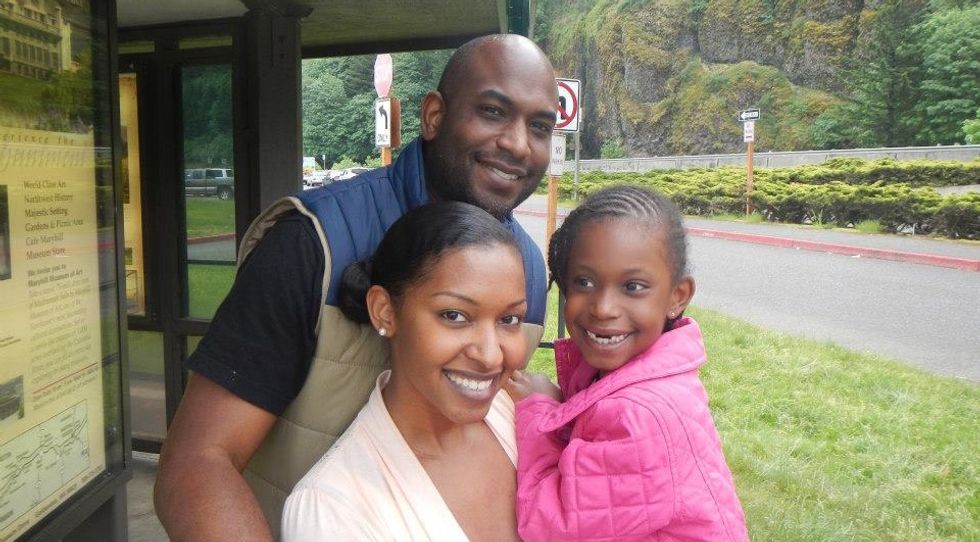

Kelsey, Klarissa and Kelis Hightower.

Photo: Kelsey Hightower

Kelsey, Klarissa and Kelis Hightower.

Photo: Kelsey Hightower

But the need for his participation clicked for him on a flight in 2017, in which he happened to be sitting in first class next to another person returning from briefing an unnamed but high-profile social media executive on the importance of diversity and inclusion.

When Hightower asked how the person had attempted to accomplish that task, the person pointed out that they were currently flying in one of humanity's greatest achievements, created by the aerospace industry. That industry, his fellow passenger told him, is even less diverse than the tech industry.

"So he said, 'If you look at this plane, it was not created by the very best that humans can do. It was created by a subset of human intelligence. The number of people who even get to work in the aerospace industry is very limited. And it doesn't reflect the absolute boundaries of humanity, it represents a subset of humanity,'" Hightower recalled.

There's just no way you're going to produce the best of everything without a little bit of everyone.

"Until people start treating this kind of diversity of thoughts, race, color, backgrounds, experience as something that can lead to the absolute best outcome, then that company will be without a doubt selling themselves short," he said. "There's just no way you're going to produce the best of everything without a little bit of everyone."

Like many of us, Hightower isn't sure what comes next in what has already been an extraordinary journey. He's had offers to run enterprise tech companies, and he serves on several advisory boards.

He closed our last interview with the story of a tech worker who learned Kubernetes while watching videos of Hightower in prison. He met Hightower at an event, and in a low voice — his boss didn't know he had been in prison — he told Hightower his story and thanked him for changing his life.

"That's how I want to be remembered," Hightower said. "I want to be remembered as this person who helped other people find out how to be better than they currently are."

Correction : An earlier version of this story misrepresented Ronnie Jordan's standing in the comedy bakeoff. He did not get second place, but in fact won. This post was also updated to correct the acquisition timeline of CoreOS.